Do you know much about the history of catalogs? Any idea of when the first catalog was printed? Want to take a guess before reading on?

If you don’t already know the answer, you’re likely imagining the old Montgomery Ward or Sears Roebuck & Co. catalogs. If you do know the answer, congratulations! You’re officially a print nerd.

So when was the first catalog printed? 1498. Let’s take a look at the long and rich history of catalogs.

The First Catalog

Caption: An illustration from c.1895 believed to represent Aldus Manutius, showing works done on his printing press. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Aldus Pius Manutius founded The Aldine Press in Venice in 1495. He printed small portable books, called enchiridia, of Greek and Latin classics. (Fun fact: Manutius is the inventor of italic font.) He was a strong believer in sharing information with a broader audience, and worked to make these books accessible to more. Before his efforts, books were extremely rare and precious items. The Aldine Press helped change this, printing more than 100 editions between 1495 and 1505. Manutius’ enchiridia can be considered a predecessor to the modern paperback. The profuse output is likely what led to the first known trade catalog in 1498.

Thus began the long and rich history of catalogs.

Seeds of Change

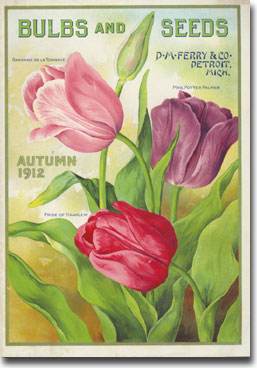

The sale of seeds and plants plays a significant role in the history of catalogs. The first known garden catalog was created by Dutch grower Emmanual Sweerts. It appeared at the 1612 Frankfurt Fair and featured 560 hand-tinted images of the flower bulbs he offered for sale.

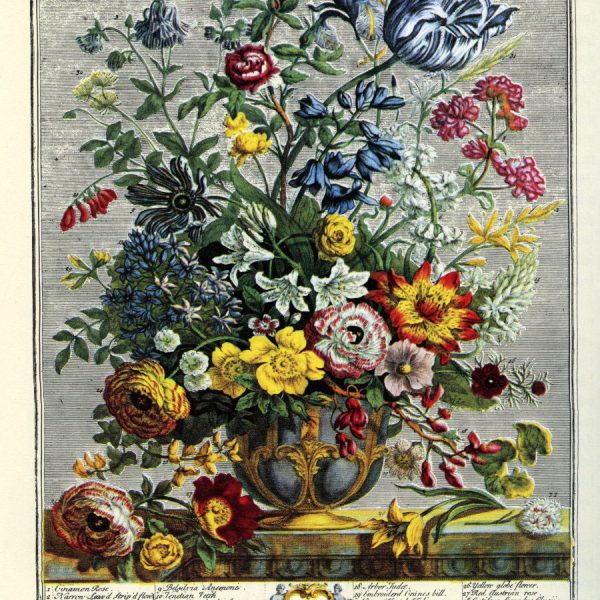

Twelve Months of Flowers, an illustrated English flower catalog from 1730, shows breathtaking images of bouquets. Creator Robert Furber sold the catalog to royal and aristocratic customers by subscription. Catalogs have long been tied to luxury. Customers had the option to purchase uncolored or painted sets. These catalogs were works of art created by Flemish artist Pieter Casteels.

The New York Linnaean Botanic Garden was the first major commercial nursery in the United States. It was founded in 1737 and operated until about 1865. The nursery was even visited by George Washington. Their first catalog was published in 1771, offering a selection of fruit trees.

These seed and nursery catalogs often featured beautiful illustrations. And it seems the publishers weren’t shy about adding their personal opinions in the pages. “Ladies should cultivate flowers as an invigorating and inspiring out-door occupation. Many are pining and dying from monotony and depression, who might bury their cares by planting a few seeds,” wrote D.M. Ferry in the 1876 Seed Annual.

(Fun fact: the first cactus catalog in the United States was published in 1886. Hints on Cacti, from Belgium-born cactus dealer Albert Blanc was “a combination cultural guide and trade catalog.” That sounds a lot like the magalogs of today!)

Catalogs Pick Up

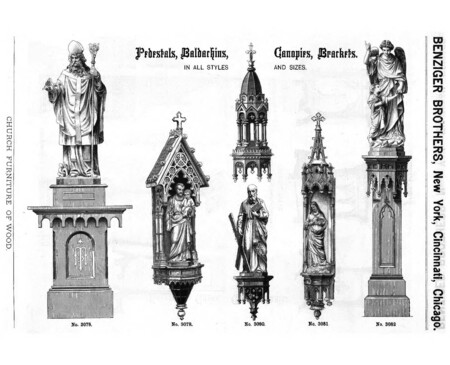

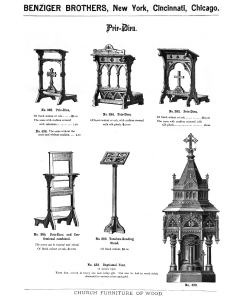

Caption: Page from the Benziger Brothers catalog of church furniture. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Catalogs picked up in the 17th century. The first instance of mail order is credited to Benjamin Franklin in 1744, but it wasn’t until the 1830s that the practice became common. It’s during this time in the history of catalogs that the now-iconic Sears, Roebuck and Co. and Montgomery Ward catalogs appear.

Sears B2B Example

The Tiffany and Co. “Blue Book” was first, debuting in 1845, but Sears, Roebuck and Co. was biggest.

Founded in 1886, with their first catalog published in 1894, by 1916 Sears, Roebuck and Co. mailed more than 50 million catalogs annually. The catalog featured detailed, accurate images of the products that were engraved directly from photographs of those objects. The entries also included detailed descriptions of the items for sale. (Fun fact: most of that copy was written by Richard Sears himself until he retired in 1908.)

When the U.S. Mail began offering Rural Free Delivery in 1896, the effectiveness of these mail-order catalogs increased. Almost anything could be purchased via mail-order catalog. Sears, Roebuck and Co. sold everything from houses to horseshoes, while more specialty catalogs flourished as well.

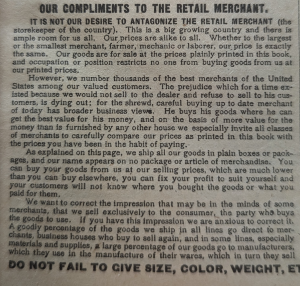

Both B2B and B2C catalogs were widespread during this time. For a long time, the Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalog served both a B2C and B2B audience. They sent their catalogs directly to consumers, but supplied to merchants as well. A 1909 catalog reads, “We want to correct the impression that may be in the minds of some merchants, that we sell exclusively to the consumer, the party who buys the goods to use. If you have this impression we are anxious to correct it. A goodly percentage of the goods we ship in all lines go direct to merchants, business houses who buy to sell again, and in some lines, especially materials and supplies, a large percentage of our good go to manufacturers, which they use in the manufacture of their wares, which in turn they sell.”

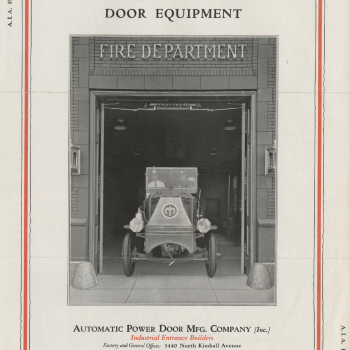

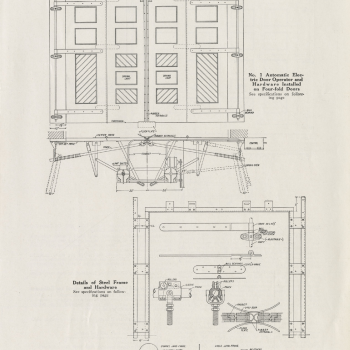

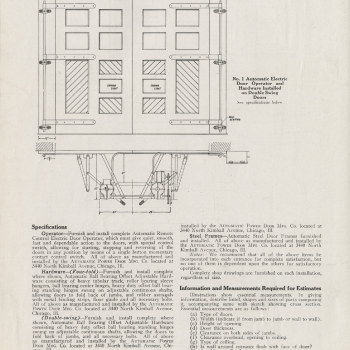

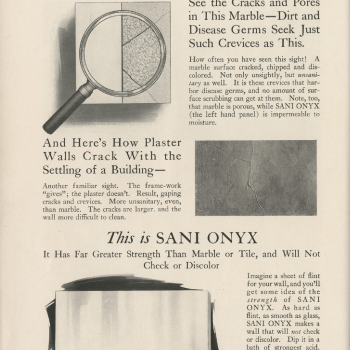

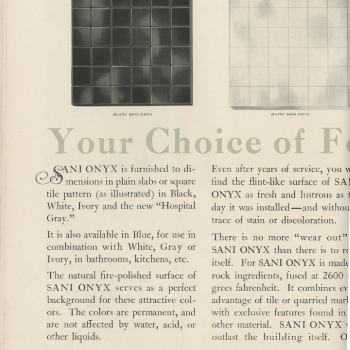

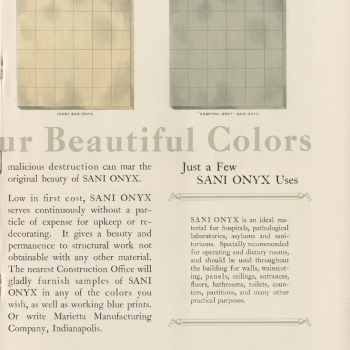

Other B2B catalog examples we found include Benzinger Brothers Church Furniture, Automatic Door Equipment and a piece from Marietta Manufacturing Co. titled “The Story of Sani Onyx: A Vitreous Marble for Hospitals.”

Cover and pages from the Automatic Power Door Mfg. Co., circa 1912. Images courtesy of Ball State University. Click each photo to enlarge.

Post-War Consumerism and the Rise of the Mall

The growth of the suburbs and construction of shopping malls following World War II had a massive impact on consumer culture. American consumerism had started after the First World War, but really took off in the 1940s, 50s and 60s.

Wages increased, young people had more disposable income and people had more leisure time than ever before. This created a demand for consumer goods. Sears, which had previously sold solely via catalogs, opened its first brick-and-mortar store in 1925. By the 1950s the company had opened more than 700 stores in the United States. J.C. Penney, which had previously sold only through its physical locations, launched their first catalog in 1963. The two mediums didn’t fight each other for sales. Rather, the in-store and catalog experiences played off each other to benefit sales.

The Heyday of Mail-order Catalogs

The popularity of mail-order catalogs peaked in the 1980s. This 1982 New York Times article about lingerie catalogs is a fun time capsule with elements that still ring true today. The focus on luxury is something modern printed catalogs are finding success with. One jaw-dropping figure stands out: “The Victoria’s Secret catalogue [sic] now accounts for about 55 percent of the company’s annual sales of more than $7 million, which explains why other catalogues are patterned after it.”

(Another fun fact: catalogue is still the preferred spelling in the U.K., while Americans abandoned it for the much easier catalog. The shorter spelling first appeared around 1880 and overtook the traditional spelling around 1970, although some people in the U.S. still use catalogue today.)

In the 1990s, the Delia’s catalog stood out. It used a magalog approach, combining sales pitches with stories. And they understood their target audience – young women ages 10 through 24 – and how to appeal to them.

The Great Recession

A couple of factors came together in 2007 that negatively affected the trade catalog industry. The U.S. experienced a recession as digital marketing and online shopping were becoming more popular. Many catalogs went online-only, but that trend didn’t quite stick. Now, even online retailer Amazon puts out a great holiday catalog.

The Future

Printed catalogs have a bright future. Consumers face a near-constant onslaught of digital distractions. Print cuts through the noise (sometimes that noise is even literal!), allowing consumers to sink into what’s displayed on the pages.

Much like retailers learned to combine the power of brick-and-mortar stores with catalogs in the mid-20th century, catalogers today are learning to combine the power of digital access with printed catalogs. With QR codes, augmented reality and the pervasiveness of smart phones, it’s easier than ever. The enormous amount of information available about specific customers also means that catalogs can be tailored for the reader.

If you’re ready to explore innovative ways you can stand out in the long history of catalogs, reach out to us to find out more about our catalog printing services.